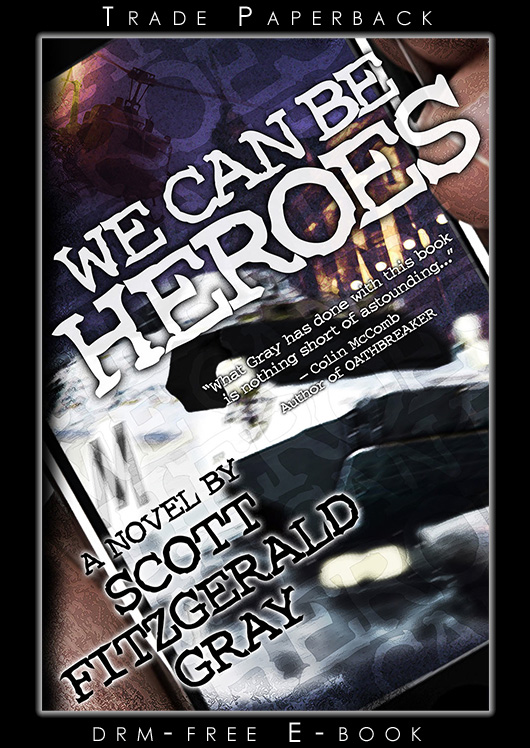

FREE FICTION — An extended sampling of We Can Be Heroes

Parts 1 through 4 of Scott's novel We Can Be Heroes (roughly the first third of the book) are available online and as free downloadable PDFs.

Part One — Also available in PDF

![]()

Red Rider, 1981. This is a story that wasn’t supposed to get told, but not for any of the normal reasons that stories don’t get told. Which is to say, there are reasons why I shouldn’t tell you what I’m about to tell you. But in a weird way, the reasons why I shouldn’t tell you the story are all things that would normally conspire to make me want to tell you the story that much more.

Sorry, that made sense when I thought it. I’ll try again.

This is a story that a lot of people don’t want told. It’s a story that was supposed to be secret, and which a lot of people would probably like to see stay a secret even after everything that’s happened. All the things that aren’t actually true, and which you’ve already heard about. Unless you were somehow disconnected from cable news and the Internet in mid-May, when it all happened.

My thing is that I don’t like secrets all that much, especially not when the secrets are being kept by powerful people. Power and secrecy have always been a really bad mix, even when things like extraordinary renditions and tabloid-news phone hackingaren’t popping up to drive them like a spike into the public consciousness. Power and secrecy feed on each other in a sort of catalytic cycle, one strengthening the other as it’s consumed, then both regenerated again to strengthen the next reaction. (Confession. I dropped Chem 11 last year after a month. I think that’s what the catalytic cycle is, but I’m not going to stop to look it up.)

(The reason I’m not going to stop to look things up here is because I need to not stop with this. I’ve never written anything like this before, so I have no real idea what I’m doing or how long it’s going to take. But no matter what I end up doing, this is the truth as it exists in me, so there can’t be any going back. There can’t be any editing. There can’t be any embellishment by running to Google to make it look like I know more than I do. Though by way of advance warning, I might let that last rule slide if I need to figure out how to spell something, because I’m kind of obsessive that way.)

In the end, what we don’t know is as important as what we do know.

Secrecy is bad. Trying to hide what we don’t know is the worst kind of secrecy, because those are the secrets we keep from ourselves.

This is a story that a lot of people will try to pretend is just crazy. They’ll try to pretend that it’s all made up. And the point is, all of that is pretty much just an invitation for me to tell the story, because the stories that the powerful people want kept secret are usually the only ones worth telling. But if the story hadn’t happened, I wouldn’t have told it. And not just because I couldn’t have told it if it hadn’t happened (because it wouldn’t have happened, obviously).

This still isn’t working. Hang on.

Before it happened, I wouldn’t have told this story even if I’d been able to. Because before it happened, I would have thought that my telling the story didn’t matter.

There. That works.

Because this story happened, I know what matters now.

Okay, it still doesn’t work. I can’t explain it. You just need to keep reading.

It’s easy to write something when you don’t have to worry about whether people will believe it or not.

Secrets are easy. Lying is easy.

What follows is what’s true.

Bryan Adams, 1981. Even after the fact, the pieces of what happened are like this collection of fragments that almost go together, but then don’t quite fit in the end. Like you’re trying to assemble something without the manual, and you get it looking like the picture on the box. But there are bits left over when you’re done, and you can’t figure out where they were supposed to go.

I’ve got it all. I’ve got a record of almost everything that happened to the five of us. I’ve got records of every part of Lincoln’s operation. I’ve got backups of surveillance feeds. I’ve got the military files that Carl kept, long after everyone else involved was long gone. I’ve got all the work Malkov did digging into those files himself. I’ve got Malkov’s voice log, right up to the end.

I’ve got the audio files from the night it started for us, which tell me Carl was listening.

You need to keep reading to find out about Lincoln and Malkov. You need to keep reading for Carl.

I don’t know how long Carl had been listening before it started for us. Listening, reading, watching. Phone calls, email, assignments, every article I’d ever written for Five Horsemen. (You need to keep reading for Five Horsemen.) Carl had all of it, so I have all of it now, filed and catalogued.

Mitchell calls me paranoid. Once in a while, I can pretend he means it as a compliment. Either way, I’m not paranoid. You need to keep reading for Mitchell.

I’ve also been called ironic, but as has been said by more ironic people than me, it’s not paranoia if they really are out to get you.

I’ve started to go through all of it. Earlier tonight, before I talked to Molly. It all starts off with the transcription Carl made the night it started. I wanted to skip ahead to the recording of the first time I talked to Carl, when I had no idea what was really going on. When Carl was pretending to be the person I needed to talk to, so that I’d stupidly follow along according to plan.

Only I can’t skip ahead, because even though I’ve got a full copy of the eighty-odd hours of archived video and data, all of it comes with a layer of military-specification destruct-scramble encryption that’s set to burn the files down even as I watch them. So I need to relive it like it happened. Like I’m writing this, from the beginning.

But as I start the video again, watching and listening to when it started for us, all I can think about is that I don’t know when it started for Carl.

This is where the record starts, but I want to know what happened before that. I want to know what Carl heard. I want to know what Carl saw to prompt the decision that made everything else happen.

When I talked to Molly tonight, she said to not bother thinking about it. She says to not watch any of it, but I know I need to. Molly says that people should make sense of what they know first, then worry about what they don’t know.

You need to keep reading for Molly, too. Molly’s right about a lot of things.

Elton John, 1973. I need to explain the deal with the music references, because you’re probably already wondering.

The deal is, there actually is no deal. They’re just a way to break things up, because when you’re writing like this, it’s all supposed to magically compose itself into chapters or something. Problem is, as has been said, what I’m writing actually happened, and real life unfortunately doesn’t always cut itself up into convenient chunks of narrative.

Based on the preceding pages, I’m not sure that the bits these words are being carved up into are even long enough to be called chapters. Chapterlets, maybe. Chapterillos? And even as I realize now that I’m suddenly pulling a total metafiction cop-out by starting to write about the process of writing, as opposed to just actually writing, I have no idea whether any of it will make any sense in the end.

However, in terms of asking why one particular song ends up at the beginning of one not-chapter as opposed to the next, I guess you could call it a thematic choice. Sometimes there’s a direct connection between the song and the part of the story it introduces (like with the next bit coming up that I need to stop avoiding writing, because the video in front of me is paused and waiting to show me the night it started). But most of the time it’s just about me. That’s the me who’s writing this right now, and who has to think about what happened so that I can figure out a way to put it down for you.

When I think about what happened, the memory feels like music. Memory is weird that way. I don’t know if anyone else’s mind works the same, but music can take me back like nothing else does to a place, a time, a thing I’d almost forgotten about. Music does it faster, music does it better than words, better than images.

Problem is, sometimes there are things you want to forget.

I put the songs down even though I know it’s kind of futile in the end, because the chances that you’ll just happen to be listening to the same song when I mention it are fairly slim.

Soundtracks in books would be a good idea, I think. Someone should work on that.

David Bowie, 1977. Recorded sixteen years before I was born. This is what Carl heard the night it started. It’s my mix, but I don’t think Carl knew that then, because most people don’t know that I only listen to music recorded between 1972 and 1981. You know that now, but you need to keep reading to find out why.

This is what Carl was listening to, because this is what was playing on the multimedia workstation in the computer lab, which I’m fairly sure is where Carl was listening from. I can hear it on the audio recording. I can read our entire conversation as it was logged and transcribed, not a word missed. From the darkness, you can hear every sound in the room, fast talking, four voices.

Carl already knew our names. Mitchell, Breanne, Rico, Scott.

There’s a lyric from Bowie’s “Heroes” that I want to quote here, because it’s extremely resonant to what I’m feeling as I write this and to what this story is ultimately about. But I can’t, because quoting lyrics in a story is forbidden by intellectual property laws still wired firmly into the corporate robber-baron mindset of the nineteenth century. You can talk about the song. You can describe the song as having been recorded by so-and-so in such-and-such a year, no problem. You can quote the title of a song, like I just did above. You just can’t quote a line from the song.

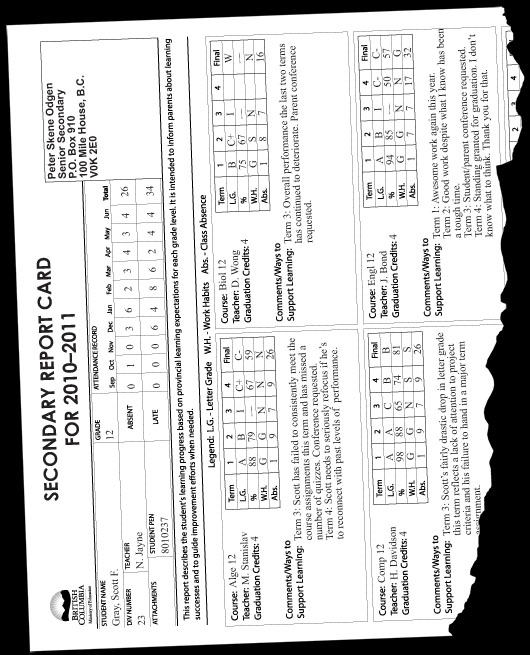

![]()

(That’s not the line from the song, because if I were quoting that line from the song I’d be in big trouble, legally speaking. So thankfully I’m totally not quoting the song, but am simply making a digression to tell you that We Can Be Heroes was the title of an ironic Australian mockumentary television series from a few years back. It’s very cool. You should watch it.)

![]()

(This is another digression. You can tell because of the parentheses. The above is also totally not a line from any song, but is the name of a pop/punk band out of Windsor, Ontario. I don’t know anything about them other than their name, because I only listen to music recorded between 1972 and 1981. Molly likes them, though.)

![]()

(Here’s another digression, in which I come to the sudden realization that this line which is totally not from any song would make a catchy title for whatever book or blog or web series this story turns into. I don’t know what this story is going to turn into. I’m just the guy trying to write it.)

The titles of these individual not-chapters tell you what I’m listening to as I write them. You can listen along if you like. Where there’s a direct connection between the song and the part of the story it introduces (like with this bit right here), you could even look up the lyrics I’m not allowed to quote. I hear the Internet is good for that sort of thing.

Bowie’s “Heroes” is a song that most people think they know, but which practically no one has ever really heard. What most people have heard is the shortened greatest hits edit or the cover versions. (Confession. I only listen to music recorded between 1972 and 1981, but I remain aware that other music exists.) However, all of those edits and cover versions skip straight to the third verse, which makes the track sound like a straightforward love song. One of those songs that makes it sound like love is a pill you pop when you’re feeling anxious. One of those songs that just really makes you want to burn a corporate light-rock radio station to the ground.

What the above-mentioned most people have all missed is the album version of the track. This includes even those of them who own the album, but who listen to the greatest-hits edit anyway because that’s what the corporate light-rock radio stations are playing when they’re not being burned to the ground.

What the album version of the song is about is two people falling in love with each other in the shadow of the Berlin Wall. What the album version of the song is about is reminding us that love, like political freedom, only really means something to those who are denied it.

(The following are not quotes from song lyrics. They are, in order, the title of a MySpace page I just tripped across completely by accident, and the title of a piece of Percy Jackson and the Olympians fan fiction. Nothing to do with anything else.)

It’s not a metaphor. It’s about living in a world in which telling someone you love them is the bravest thing you’ll ever do.

Just think about it.

I was born way too late to have grown up in East Berlin, but I often think my life would have made a lot more sense if I had.

Roxy Music, 1979. Not knowing how to start has always been a problem for me. Hence, the rambling I’ve been doing. I’m done now, though. This is the night it started.

From the multimedia workstation in the computer lab, here’s what Carl heard.

BREANNE: We head for the gangway, recon front and back. Sensor sweep, five by five.

RICO: Motion, IR, and EM spec on the hull. Looking for movement and stress points.

MITCHELL: I cycle the airlock.

Sorry, hang on a minute.

This next bit is about RPGing, but don’t panic or anything. If your eyes are already glazing over, it’s a short bit, I promise.

This bit is about RPGing, which stands for roleplaying gaming, by which I mean tabletop roleplaying gaming, which I’m going to refer to hereinafter as gaming. Because in my world, there’s no other kind of gaming.

This isn’t a story about gaming, though. Not in any important sense, anyway. The story’s about people who happen to be gamers, and about what that means to us, and what difference that made to what happened, and why. The story might have just as easily been about people who happened to play lacrosse or chess or badminton or whatever.

Though if it was, things would have turned out quite badly, I expect. And this would be a bit about listening to a badminton game. Between you and me, we’re all better off this way.

This is a story about gamers. But there are only a few places where that really matters. I’ll try to warn you in advance.

MITCHELL: I cycle the airlock.

SCOTT: As has been stated previously, the airlock is jammed. Get over it.

MITCHELL: That makes no sense.

BREANNE: It would make perfect sense to anyone with sense. The airlock is jammed.

MITCHELL: An airlock by definition is designed to withstand pressure. How does the application of pressure jam it?

RICO: You applied pressure in excess.

MITCHELL: Three lousy cluster bombs?

SCOTT: Your three lousy cluster bombs have blown the cargo hold to ribboned

Sorry, hang on another minute.

I’m writing this, and I’m typing down bits of the transcription that Carl left for me, and it’s supposed to be the truth. I’m telling this story, and it’s a story about me and the others. But the truth is that me and the others swear a whole lot.

All right, maybe not so much the others. Except for Breanne when she’s in the right mood. Me, I swear a whole lot, one particular Anglo-Saxon epithet in particular. I’m not sure why that is.

This story is supposed to be written for public consumption, though. And I know I’m not going to worry about the occasional damn, hell, and oh god sliding by. However, for the harder stuff, there’s a kind of cultural speed limit for profanity, and I’m about to blast past it even before the parts of the story that really deserve it.

But here’s the thing — either something’s true or it isn’t. Either I write things down the way they actually happened, or I might as well just be making it up. In my world, there’s no This is the truth except for the words I had to change because I didn’t want to offend anybody.

Here’s a thought, though.

We studied journalism and editor’s marks with Ms. Bond in first term English. In edited copy, if you see brackets [like this], it means that someone has inserted or amended something that wasn’t a part of the original text, but they’re alerting you to the fact that it’s been changed. So here, when you see [this], it means that the this in brackets isn’t really what was said, but that I’ve done the editor’s thing and replaced it with something.

For the most part, I’ll try to replace things in such a way that you can figure out what was really said if you want to. Like on cable TV, where they bleep the words but still let you read those words on the lips of whoever’s saying them.

SCOTT: Your three lousy cluster bombs have blown the cargo hold to ribboned rat[dung].

Subtle, isn’t it? But maybe it all makes a certain sense, actually.

This is the truth I’m telling you, and truth should always make you think about what you’re hearing.

SCOTT: Your three lousy cluster bombs have blown the cargo hold to ribboned rat[dung]. The airlock is jammed.

BREANNE: Are you eating that?

RICO: Nope. We head for the gangway.

MITCHELL: I cycle the airlock.

SCOTT: The airlock, for the last [lord’s name in vain] time, is [lord’s name in vain] jammed, all right?

MITCHELL: That makes no sense.

RICO: Somebody binds and gags the hiver, then we head for the gangway.

MITCHELL: That’s mutiny.

BREANNE: Shut up. I’m on point.

SCOTT: Spot check.

Carl would have heard dice, but that doesn’t mean anything unless you already know what you’re listening to. Dice rolled across a gaming table make a particular sound that won’t mean anything to anybody who doesn’t game. If you know that unique clatter, you can almost hear the meshing of random gears as numbers fall out and the drama spins off from them. Mitchell claims to be able to tell what numbers have come up even without looking, just from listening. Like the wonks in automotive class can tell the difference between a Ford Triton 3V and a Dodge HEMI just from the sound of them both idling a half-klick away.

(Confession. As I’ve never been within half a kilometer of an automotive class, I’m actually one of those people who can’t tell the difference. I heard Breanne give the blindfolded anecdote a couple of months back. I guessed at the time that a Ford Triton 3V and a Dodge HEMI are engines, but maybe she was talking about stereo systems, I don’t know.)

BREANNE: Yeah! Thirty-six.

SCOTT: Since how?

BREANNE: Plus-eight for the full-spec night-sight goggles I found on what was left of the crew chief.

SCOTT: Fine. Indistinct shapes fan out across the gangway. Drone destroyers, chameleon combat armor.

More dice on the audio. Someone slurps from a can of something highly caffeinated. Carl would have heard a lot of that as well.

BREANNE: Feed the closest one half a clip and scatter. Hell, twelve damage on eighteen?

SCOTT: Breanne for the miss.

RICO: Get a grenade off.

SCOTT: Don’t remember you reloading.

RICO: When Bre reconned the lifeboat.

SCOTT: Do it.

RICO: Thirty-two adjusted. Twenty-six concussion, eighteen fire.

SCOTT: You distract them. Auto-fire rounds hit behind you, four distinct patterns.

BREANNE: Follow the line of fire back at them. Pulse rifle, full auto.

SCOTT: Can’t shoot what you can’t see.

BREANNE: Night vision, Einstein. Goggles are on.

SCOTT: On, overloaded, and shut down when Rico’s incendiary went up in front of you. You going to fire blind or claw them off and call me back?

BREANNE: Oh, bite me.

SCOTT: Only if you mean it. You?

RICO: Reloading.

SCOTT: You?

MITCHELL: I cycle the airlock.

BREANNE: [Archaic epithet calling Mitchell’s parentage into question. As Breanne and Mitchell are twins, I’m not sure she really thought that one through.]

Breanne jumps up from a table spread with charts, dice, and the box that once held a takeout pizza that never stood a chance. The rest of us sit across from her. This is us.

Mitchell is a bookish savant. Hair that’s too long to be fashionable, not long enough to be metal. John Lennon glasses, well-worn Dockers, a Firefly t-shirt that’s been washed a few too many times.

Rico is a subdued bruiser. Hair short but not quite military spec. Faded jeans and muscle shirt, chiseled arms that would be a tattoo artist’s dream.

Scott cultivates what Mitchell annoyingly calls the fashionable nihilist look. Black t-shirt, black jacket, black khakis, black paratrooper boots mail-ordered from Can. & U.S. Army & Navy Surplus in Vancouver. I’m Scott.

Breanne is post-feminist chic. Hair short, overalls, tank top, Dream Theater baseball cap. Her anger toward Mitchell as she stuffs her backpack is tangible.

“I told McAllister I’d work a half-shift tonight, you [gender-specific anatomical reference]! You said you were watching the time!” She adds a number of epithets so personal that I can’t think of any brackets for them.

“I’m apparently bound and gagged,” Mitchell says. Rico’s already slamming chairs back and sweeping up paperwork in a frenzy of hiding all evidence that we’ve been there.

This is after hours in the computer lab, thirty-odd iMacs standing dark. This is the Computers 11 and 12 classroom, plus in-class and after-hours resource room for the science and math classrooms across and down the hall. We’re at the west end of the main-floor corridor of the high school, stuck in the middle of the hard-science labs like an afterthought. This is because the computer lab was, in fact, an afterthought, its inside door leading into the chem lab in a way that makes no real sense.

Mitchell and Breanne are getting into a deepening argument about who’s the responsible one while Rico tries to keep them separated. The upshot is that no one’s paying attention to me, which I find annoying.

“Hey, we’re kind of in the middle of something.”

“And I’m kind of late for work.” Breanne shovels the last two slices of leftover double-pepperoni into an empty sandwich container in her backpack.

“You’ll be dead in five minutes. Sit down.”

But she’s already out the door to the corridor, Rico dragged behind her with an apologetic shrug. Mitchell pops my iPhone from the multimedia workstation and frisbees it across the room for me to catch. I scoop dice and carefully roll up the night’s battle maps.

I hear Breanne shouting something about hurrying the hell up from the corridor. I methodically take my time.

Outside the computer lab, the school is dark, which is mostly an improvement on its look during the day. Based on a whirlwind small-town debating club tour that Mitchell, Molly, and I took last year, I suspect that there’s only ever been one small-town high school. Like one set of master plans gets passed around the circuit of rural school boards for decades on end. Or maybe a secret government star chamber determined a long time ago that sapping the will of the kids of the forest-industry working class was best done by trapping them inside this one particular arrangement of cinderblock walls.

Next to the custodian’s storage hangs a largish sign reading Peter Skene Ogden Secondary School ~ École Secondaire. The name is wrapped around the school’s majestic mascot, which is a vaguely manga-esque bald eagle, which is a bird that gets terrorized by crows a lot, and so is a lot less majestic than most people think. Peter Skene Ogden was a nineteenth-century fur trader who lied, stole, vandalized, assaulted, and murdered his way across the North American frontier. He left behind him a legacy of brutal violence, environmental destruction, overt racism, multiple wives, and illegitimate children, though it’s never been clear to me which of these accomplishments landed him the coveted having-a-high-school-named-after-you gig.

Across from the office and the main-floor foyer, a glass display case is filled with trophies and newspaper clippings. The highlights of the various school teams that come and go with the seasons are kept track of here, along with occasional mentions of less athletic honors. Mitchell, Molly, and I were in there last year when the debating team took second place at the regionals in Prince George.

Last October, the five of us took first place in the VCON RPG team open in Vancouver, but nobody bothered posting that anywhere. Maybe if we’d had school uniforms or something.

The five of us means me, Mitchell, Breanne, and Rico, plus Molly. You need to keep reading for Molly.

Along the ceiling, security cameras are mounted at regular intervals, wide-angle lenses covering every part of the corridor. Or at least they would be if they were ever turned on. The cameras were installed last year in the main hall and the downstairs lockers after a rash of brazen iPod thefts. That is to say, after one iPod theft from Mr. Mueller the phys-ed teacher, who accidentally left his backpack at the downstairs water fountain one day, then screamed really loudly about it.

However, it turns out that although you can video-record students in the corridors stealing each other’s iPods without their permission, you need their permission to actually look at that video in order to catch them at it. Privacy law’s a funny thing.

As Mitchell and I follow Breanne and Rico toward the main doors, we pass along an endless wall of glassed-in photos where dozens of previous generations of graduates hang. Most of them have this identical expression that suggests they’re all trying to project a mature and confident gaze toward the future. Problem is, none of them ever suspected that the future doesn’t like to just stand in front of us waiting to be gazed at. The future likes to pick a really good spot, out of sight and just to the side. Then it hangs there with a sniper rifle and a really good scope.

I’m betting the people in the photos never saw it coming.

At the end of the month, somebody will pull the oldest array of mugshots down. That’s the class of 1982, who for some reason have always seemed to look particularly stunned even compared to everyone who came after them. Then they’ll shift all the frames down to make room for the new mugshots. Mitchell, Breanne, and Rico will be there. Molly will be there.

As Mitchell and I descend the east stairs past the library, Breanne and Rico wait inside the back-door foyer that leads to the student lounge. Breanne is pacing relentlessly while Rico stands in his usual stolid way. Because they’re holding hands, this means she has to make a sort of horseshoe orbit around him in an agitated fashion.

“Don’t let us keep you,” she calls loudly.

“Wouldn’t dream of it.” I flash her the confident smile that comes from being the only one in the group who knows the alarm code, which let us open the doors without calling down a police action on top of us.

I key the alarm off. Breanne is in a big enough hurry that she doesn’t bother trying to get a look at the code like she usually does. I toss Mitchell the pizza box for the recycling dumpster at the edge of the student parking lot, our bikes chained a few meters away. The aging crew cab pickup that Rico’s dad bequeathed to him for his birthday last year is the only vehicle there, he and Breanne already sprinting for it. I set the alarm again, locking the door behind me as we go.

Thin Lizzy, 1975. Mitchell and I are cycling across the school field, paralleling the side road where it feeds into the highway ahead. Breanne and Rico roar past in his truck, Deckard & Sons Excavation & Landscaping emblazoned on the box. An airborne haze of road dust rises behind them. Rico waves. Breanne waves, too, but with fewer fingers.

Where Mitchell pedal-stands behind me, I call back. “You thirsty?”

“No.”

“You’re not thirsty?”

“No.”

“I figured you might be thirsty.”

“Well, let me think. No.”

I lead on. Behind us, the school recedes on its perch along the highway hillside. A truck yard stands adjacent, the RCMP station closer to the highway, the town and its two thousand people spreading below. This is vintage interior-British Columbia logging country, stands of Douglas fir and white spruce, aspen and lodgepole pine spreading to every horizon, the late-spring sky immense overhead.

It’s a short jaunt off the field and through an obstacle course of brush and discarded fast-food debris. Then an exhilaratingly rough ride takes us down the trail that runs past the pedestrian underpass beneath the highway. A steep slide down a gravel bank leads alongside the broad spread of marsh and bird sanctuary that opens up smack in the middle of town.

Beyond that marsh and the small airstrip that stretches alongside the marsh, the arena, and the curling rink, our destination is Howie’s Corner Store. It occupies the center of a dusty stretch of frontage road, meaning it isn’t actually on a corner. Just think about it.

We do business quickly enough to make sure the bikes don’t get stolen, and I’m out before Mitchell so that I can claim the piece of sidewalk I want to claim. His look when he exits behind me has disapproval written all over it, but the sugar rush from the slush I’m knocking back dulls it for me.

Howie and Maureen, the not-on-the-corner store’s cheerily wholesome thirty-something proprietors, eschew any sort of Slurpee mass-productionism to make their slush the old-fashioned way that nature intended. That’s unflavored ice and a self-serve syrup bar that they have no apparent problem with me overloading from. There’s probably slightly more sugar than water in the mango-lemon-cola slam-mix I’m partial to, which is also as nature intended.

Overhead, sunset streaks a darkening sky. On the highway, a steady stream of traffic runs the amber light at the intersection with Fourth Street. Across and to the left is the Exeter Arms, which is a hotel whose parking lot overflows with patrons for the bar most nights, but which doesn’t do any actual hotel business that I’ve ever been aware of. To the right is a mirror-image frontage road to Howie’s frontage road, on which sits a darkened realtor’s office, an open-late-but-about-to-close thrift shop, and a store that seems to be perpetually for rent. Or maybe they sell For Rent signs. I’ve never actually gone in to see. Closer than all the rest, Brownies Chicken anchors the corner.

“Do you ever feel like you’re living in the wrong time?” Mitchell asks as he appraises the sky.

“Pretty much constantly.”

Mitchell slips onto his bike with a chocolate milk and a stack of sesame snaps in hand, then does this thing where he pulls his feet up to the pedals and just kind of balances there without moving. It’s impressive. I timed him going to four minutes once without having to touch down on the ground, but I wasn’t interested enough to see how much longer he could make it.

“Say you can go anywhere, anywhen,” he says.

“Dallas, November 22, 1963. With a six-person HDCAM crew covering multiple angles with really long lenses.”

“It’d be thirty years before you could sell it to CNN.”

“I’d wait.”

Across the highway, through the Brownie’s plate glass, I can see her.

Behind the counter, Molly looks distracted as she comes on shift, slipping her uniform top over a long-sleeved white sweater and jeans. At eighteen, she’s a year older than Breanne, Mitchell, and I, but she’s always managed to look younger somehow. Something in the way she used to laugh, and in the spread of pale freckles that clouds her nose. Something in the blonde hair that’s tied back in a ponytail now like it usually is, and which always seems to be moving in slow motion.

(Confession. Technically, Molly is only nine months older than Breanne and Mitchell, who will catch up to her and Rico both in October. She’s eleven months older than me because my birthday’s in December, meaning that pretty much everyone in my grade has always been older than me.)

I pick this particular patch of sidewalk like I do every other time Mitchell and I stop here, because it sits in the shadow between battered streetlights. From that shadow, I can watch without being obvious about it. From the corner of my eye that isn’t watching, I see Mitchell follow my gaze.

“Hanging out here night after night watching an ex-girlfriend sling fried food is a sign of some serious sociopathy in progress.”

Mitchell has never been one for needing things spelled out. As such, he’s the one person I’ve never bothered to refrain from showing my irritation for spelling out the things I prefer to deny.

“Considering she was never my girlfriend, is there a reason you keep calling her that?”

“Because it was what it was whether the two of you got around to calling it that or not.” He shrugs, balancing with one hand on his handlebars as he drinks. I’ve known Mitchell long enough to know that him shrugging is a tell, like in poker. It’s the only sign he’ll ever give that he cares about a problem that he knows he can’t fix, so that he won’t try. “The game was better with five,” he says.

“Talk to her about that.”

“Sounds easy.”

I give him the same wave Breanne gave me, just as the sugar rush and the brain freeze meet in the center of my occipital lobe like they always do. Through my euphoric stupor, a thought takes form as words even before I’ve had time to think them through.

“She ever say anything to you?” It’s been four months, and I haven’t asked that question of Mitchell yet. I’m pretty sure that’s because I already know the answer.

“No,” he says, which means I was right. “Breanne said they talked.”

“What about?”

“About how she didn’t want to talk.”

I feel like there’s something else I want to say, but all I can do is watch.

This is what I see.

Through the window, through the haze of taillights that brightens as the sky overhead gets dark, Molly clears tables. Brownies is only half-full, like it mostly is outside the lunch and dinner rush. As she works, she dances to edgy alt-prog rock on the CD jukebox, looking like she doesn’t care who’s watching.

Beyond the lights of 100 Mile House, which is usually shortened to 100 Mile in the writing and is only ever called Hundred Mile by anyone who lives here, broad slopes of forest and rangeland spread to all sides. Where the highway sweeps down, then up again along those slopes, you can look up along the line of forest and sky, letting the stillness and the size of the night just take your breath away.

When the sun sets here, it’s like the world hangs for an endless moment between light and dark. Like the landscape is watching the day fade away but isn’t ready for night yet. Watching the lights come on along the side road and the hotel parking lot and the Brownie’s sign across the highway. The Brownie’s sign is a giant bucket of chicken, lighting up like some lurid beacon of civilization in a dark wasteland.

(Sorry, that’s too much of a stretch, even for metaphor. Never mind.)

“What about you?” I say to Mitchell.

“What about me?”

“The right time and place for you.”

“I don’t think it exists. But at least here and now, my chances of getting burned at the stake are low.”

“You might be surprised.” I drain the last of my slush and carefully crush the cup.

“Seriously,” Mitchell says. “A movement toward real consciousness is at work these days. The consumer state is crumbling as the media veil begins to short-circuit itself, and McLuhan’s medium is the message that’s burning out with oversaturation. We live in an age of ontological instability and evolutionary imminence.”

“We live in a police-state prison where guards and inmates trade off jobs on odd days.”

“You do know that optimists live longer?”

This was when it started, even if I didn’t know it then.

I hear it first, the faint drone twisting through the traffic noise. Then I look up. A black helicopter comes into line of sight, shooting past fast overhead, southwest to northeast. Low enough that its lines are sharp against the sunset, burning copper along the western horizon.

“And did you know that there are currently upwards of three hundred private paramilitary organizations active worldwide?” I say.

“I must have missed it with Keith Olbermann off the air.” As Mitchell follows my gaze, something in his sense of balance doesn’t like the view. His foot touches the ground as the bike shifts beneath him. He looks disappointed.

“Black helicopters,” I say. “No markings. You can find them in any country in the world, moving with complete freedom. Weapons dealing, espionage, sabotage. The line between military and business erased because that’s the way the power brokers want it.”

The chopper is directly overhead now, louder. Mitchell squints. “Or maybe a German package tour gets to take in the sunset at a hundred bucks a head.”

“You have any aspirations beyond just being really naive all your life?”

“I’ve actually come to the conclusion that aspiration itself is meaningless in the long run.” Mitchell is staring past the chopper to the sky, his gaze distant like it gets when he’s thinking. “We all long for glory, but our greatness is constrained.”

“Speaking for yourself?”

“I’m speaking for you, actually. I see you slowly strangling inside your cynically twisted worldview.”

“And what’s holding you back?” I ask.

“The distraction of a perfect knowledge of what it is holding everybody else back.”

“Glad I can be a part of that for you.”

I stand and dust myself off. Across the way, Molly is dancing past the side windows, clearing trays as she nods to an older couple at a corner booth. She doesn’t smile. Molly doesn’t smile much anymore.

“Show’s over?” Mitchell says.

“Ride, Aristotle.”

I hop onto my bike and head out on the frontage road, fastening my helmet with one hand so that it blocks my face from the Brownies side of the street. Not that Molly would be watching anyway.

I don’t need to turn back to feel Mitchell looking from me to the distant windows before he sprints to catch up.

Alice Cooper, 1981. I’m watching this on a set of matched video streams. External night-vision flight tracking, plus the chopper’s interior surveillance feed. It’s logged and encrypted with all the rest of the recordings, but if it wasn’t for the time-stamp on the feed, I might not get the full significance.

While Mitchell and I were talking, this is what was being recorded high overhead.

Through a night-vision lens in the chopper’s belly, 100 Mile is a dark scar of urbanization cutting through an endless expanse of wilderness. If you look closely, you can make out the bright suture scratches of roads that hold it all together. If you could up the resolution a couple of times, you’d see the bright points of Mitchell and I on the sidewalk, staring up.

In the cabin, a guy sits in the pilot’s seat, forty-something in a black leather jacket and sunglasses. This is Lincoln. Behind him, a half-dozen men and women ride, sleeping or reading or looking bored where they watch out the windows. They’re all decked out in casual business garb, maybe a group of forest-company middle managers coming back from an asset survey. That’s what you see if you don’t look too closely.

But if you do look closely, you’ll notice the woman riding shotgun beside Lincoln. She’s dressed in some buttoned-down one-martini-lunch number like the others, her dark hair tied back.

Her name is Karya. In the unmoving field of view that the cabin camera makes, she’s fieldstripping an Uzi as Lincoln takes her and the others home.

Heart, 1976. Mitchell and I take a long detour through the Esso parking lot on our way through town, because I’ve got a slow leak in my front valve that I can’t be bothered to fix. While we’re there for air, I see what follows.

The Esso station sits off the highway at the north edge of town, a little island of light and signage in a larger sea of light and signage. Across from the newer mall, it’s a stone’s throw from the Red Coach Inn, which is probably the closest thing this place has to a landmark. 100 Mile House is so named because it was originally a stopover post one hundred miles up the road from Lillooet, where the B.C. gold rush trail north to the Klondike started. The Red Coach is so named because it has a horse-drawn-style red coach out front, much like the ones people used to ride back in those days.

In the years since the gold rush, they’ve straightened the highway a couple of dozen times, so I have no idea how many miles it is to Lillooet anymore.

I remember Mr. Palmer in Social Studies 10 talking about when Canada adopted the metric system, and how there was a huge concern about whether the government would force the town to change its name to 160.9 Kilometer House. I’m pretty sure he wasn’t joking.

As is often the case on a weekday evening at the Esso, Rico can be seen greeting customers at the pumps. This is odder than it looks, however, as it isn’t Rico who actually works at the Esso weekday evenings, but Breanne. Only whenever Rico’s there, she spends most of her time under the hood of his truck and counts on him to cover for her.

Breanne under the hood of a vehicle is a thing I’m not qualified to write about. She moves really fast is about all I can say to describe it. She whips around a lot of tools without actually looking at them. Then when she’s done, whatever vehicle she’s been under the hood of runs better than it ever did before.

As Mitchell and I ride up, a lull in the steady stream of traffic lets Rico saunter over to where Breanne is a blur of mechanical-savant motion. They both see us and wave. Breanne uses more fingers this time, so I know I’m forgiven from earlier.

“Are you planning on pumping any gas tonight?” Rico calls to her.

Breanne’s voice is muffled as she leans in, hanging by her hips over the edge of the engine well. “Are you planning on ever paying me for this exclusive automotive service thing we seem to have going?”

“I’m waiting till you break something. Your rate will probably improve.”

Breanne laughs. “Hey, I sent my SAIT application off.”

Mitchell is balancing again as I try to get the pressure gauge on the pump to decide whether it wants to work or not. SAIT is SAIT Polytechnic, or the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology. They apparently teach people how to fix cars there, judging by what Breanne says as she hops off the truck to throw things back into an oversized toolkit. “The automotive program is supposed to be amazing, and then Marnie Robison’s cousin manages the Canadian Tire in Red Deer. She says I can stay with her while I apprentice.”

“Yeah,” Rico says, because that’s what Rico says. I’m the only one looking at him when he says it, and I see a sudden tension in the way he’s standing, the lines of his crossed arms expressing emotion that the silence hides. It tells me he doesn’t see me watching. I look away to make sure he doesn’t.

“Because I think Regina’s probably your best bet,” Breanne says, “because then you do the justice program instead of the criminology, because everybody and his dog has a criminology degree. And the team’s not great, but that just means less competition for captain, right?”

“Yeah.”

My tires are topped up. Mitchell and I head for the highway.

“You’re a man of many words tonight,” Breanne says, but Rico is peering under the hood as she pulls it shut. “Treat your engine nicely, it’ll treat you nicely. There’s a lesson in there.”

“Yeah,” Rico says. Then he says, “I love you.”

Despite the fact that it has nothing to do with me, this catches me off guard. Because it’s something I’ve never heard Rico say before. Then Breanne says it back, and I suddenly feel like I’m intruding in something I shouldn’t be. The two of them are leaning close and talking some more, but I turn my attention to the highway, moving past them and out of sight.

As I approach Mitchell where he waits for the light, I glance back to see Rico and Breanne kissing with a particularly teenaged intensity. Another car pulls in, Breanne glaring at it as they kiss again. Then she waves goodbye as she heads for the pumps, Rico climbing into the truck and starting up.

I’m the only one who sees him watching Breanne for a long moment before he goes.

Kansas, 1977. I didn’t see this. Molly told me.

She didn’t tell me till tonight, where tonight is when I’m writing this. It’s already a few days later than it was when I started writing, and for the record, I still have no real idea what I’m doing.

I’m stalling for time because I don’t want to write this, but this is where it needs to go.

Outside Brownie’s, it’s dark now. Inside, a different older couple are eating at the corner booth. A gaggle of junior high students are at the counter, stopping by before the late show at the Rangeland. The Rangeland is the one movie theater we have in town. It’s up the hill, past the older mall. That’s got nothing to do with Molly. I’m just mentioning it because I’m stalling for time. Because I don’t want to write this.

While Sal the manager works out front, Molly’s in the break room behind the kitchen, whose side door opens onto the short stairs to the parking lot. Last year, when Molly started working at Brownies, I used to wander down and sit on the steps with her while she took her breaks. I don’t do that anymore.

This night, the side door is open because the deep fryers in the adjacent kitchen and the spring chill outside cancel each other nicely. Molly sits straight-backed on the couch, playing my old PlayStation 2 system hooked up to the break-room TV. She talked me into giving it to her last year because I wasn’t using it anymore, and because Sal’s antenna reception always had slightly more static than picture on the two broadcast channels you can get in 100 Mile. She’s playing Ace Combat 4, which is a little on the vintage side but can still surprise you. Unless you’re Molly, that is.

Like I can’t describe Breanne at work, I can’t really describe Molly at a combat flight simulator console. I’ll give it a shot, though.

Molly’s reflexes are staggering. Her connection to the controls is like something organic. Watching her fly is like watching one of those time-lapse video clips of plants growing. You recognize the movement, but it’s all too fast somehow. She gets to this point where she doesn’t even blink, her eyes shining like some kind of blue

Sorry. I can’t do it. I’ve never had the words to talk about Molly’s eyes.

Whatever mission she’s playing, Molly’s speed and altimeter readings will be clocking over as a blur of digits. If she’s playing the mission she likes best, she’s soaring over an expanse of anonymously rendered could-be-Siberia/could-be-Iraq post-apocalyptic scrubland cityscape, pursued by enemy jets coming in from six different directions. That scrubland cityscape spends most of its time at the top of the screen as Molly dodges missile tracking and anti-aircraft fire upside down, a succession of tight rolls letting her unleash fiery death in a wide arc around her.

But then even in the midst of narrowly avoiding what seems like certain destruction in a web of heat-seeking missiles and machine-gun fire, Molly falters. She hits pause on the controller, standing quickly in response to the figure ascending the stairs from the parking lot.

Victor is Molly’s dad, though he’s actually her stepdad. Which is to say, he’s been her stepdad for a long time and she calls him dad. You know what I mean. I can’t talk about Molly’s real dad because it’s not like Victor’s imaginary, but Molly’s original dad died when she was a kid. She doesn’t talk about him very much.

Victor is a business-lawyer type, better dressed even at this hour than most people in town have any reason to dress during the day. There’s a self-consciousness in Molly suddenly. All the fluid grace that normally flows from her into a game controller is gone. She can hear Sal and a customer laughing about something out past the kitchen.

“Hi,” she says.

“Not keeping you, am I?”

Victor has this voice. I haven’t had to hear it for four months now, but he’s got this voice with a kind of withering tone that makes you want to wash your ears out with bleach.

“No,” Molly says. “Would you like some coffee?”

“Is it any better than it usually is?”

It’s not an attempt at humor. Victor’s voice doesn’t do humor.

“I don’t know,” Molly says quietly.

“Then I guess I don’t. Are we going sometime?”

It takes Molly a second to understand.

“I’m on until ten, actually…”

“You told me eight.”

“I don’t think I did. I mean, if I did, I’m sorry.”

“Me wasting a trip into town, what’s that to be sorry about?”

Victor’s voice also doesn’t do anger. Victor is very careful to never let the anger show.

“I didn’t think…” Molly says.

“Yeah, you covered that.”

And he turns away, quietly descending the steps where Molly and I used to sit. Victor doesn’t like to make a lot of noise.

Molly watches through the open door as he hops into the well-kept SUV he’s left idling in the parking lot. She tosses the controller aside, switches the TV off as he pulls away.

Supertramp, 1979. Mitchell and I ride for the better part of the evening, because that’s what we do. Through the straight grid of empty downtown streets to start with, we swing down Birch Avenue past Games Galore. That’s the local gaming and comic shop that I’m pretty sure the four of us, who used to be the five of us, keep in business. Ken and Lynne are the couple who own and run it, who are kind of in the same ballpark as my parents in terms of age but cool to point that I only desperately wish my parents could be.

After downtown, we hit the trails through the park as a crescent moon breaks from the clouds and adds its light to the sodium glow of the parking-lot floods. As we ride, we engage in an endless ongoing conversation of story and game and narrative, because that’s what we do. Imagine laying out and mentally scripting a film of no specific genre, scene by scene. But don’t worry, I’m not going to bore you with it.

(Confession. I know absolutely nothing about filmmaking, so I have no idea what’s involved in scripting a film. I just know that what Mitchell and I can come up with in an hour’s night riding is a whole lot more entertaining than anything I’ve ever seen on screen.)

Mitchell’s due back home at ten, so that’s when we pack it in. I ride to his place to drop him off, which leaves me with the long trip back home. However, the silence and the darkness don’t feel like a bad thing this night. On top of the annoyance of having to jam early on the reactor-crippled starship firefight I’d prepped that afternoon while skipping English, the conversation out front of Howie’s is bothering me more than I want to admit.

I wasn’t there to see what happened after I dropped Mitchell off, and I wasn’t at Rico’s that night, but I’ll lay things out anyway. You’re going to see my house in a minute, too, and the scene at home doesn’t ever change all that much for any of us.

Breanne and Mitchell live with their folks, Malcolm and Kim, in a cabin two klicks or so out Horse Lake Road. Malcolm and Kim are former antiestablishment socialist punks from the first time the punk thing came around. In their house, bookshelves and agit-prop political posters line the walls beside a woodstove that burns almost year-round just for the ambience. Breanne will have been picked up from the garage by the time I drop Mitchell off.

While everybody dishes up a late dinner, they’ll talk about a food-bank drive, or the community garden project just starting up, or a hospital benefit, or some other cause of good will. As they eat, Breanne and Mitchell will attempt to throw responsibility for whatever volunteerism their parents are looking for onto the other person. They’ll be doing this with practiced ease. Mitchell and Breanne have spent their lives defining themselves in terms of stark opposition to both their parents and to each other, which involves a kind of four-dimensional Boolean algebra that can’t really be explained. Not that that stops Mitchell from trying.

Rico’s parents are Vern and Shelley. They live in a two-storey place that overlooks the park where Mitchell and I were just riding, and whose size suggests that they’re waiting in vain for Rico’s two older brothers to move back home sometime soon. If this night’s like most nights, Rico’s mom will have apple pie on the table before bed. You can smell the highly addictive brown-sugar scent of Rico’s mom’s apple pie from six blocks away. The actual taste of Rico’s mom’s pie is another thing I can’t describe.

Rico’s dad will be sitting back with his suspenders half on and the accumulated grime of thirty years’ honest landscaping labor still on his hands. He’ll be poring over this year’s John Deere heavy equipment catalogue and asking Rico what he thinks of the ProGator 2030A. Rico will tell him what he thinks, quite knowledgably. I find that very unsettling.

(Confession. I know there’s something called a John Deere ProGator 2030A because it was featured prominently a couple of months back on a billboard at the heavy equipment dealer across the highway from the school. I have no actual idea whether Rico’s dad would ever need one, but I thought it sounded good.)

The last time I was at Rico’s, a seven-month-old newspaper clipping was still taped to the fridge, next to his mom’s church circle notices and a recipe for sausage gravy. It’s the bottom-of-page-14 100 Mile Free Press article about the five of us winning the VCON RPG team open. It’ll probably still be there long after Rico’s moved out.

Here’s a screenshot from the Free Press website.

Richard is Rico, but you probably figured that out. Mitchell has his dad’s last name as a last name and his mom’s last name as a second middle name, and Breanne vice versa, because their parents are former antiestablishment socialist punks. Yeah, the article spelled my name wrong.

Molly lives with her dad at 108 Mile, in a business-lawyer-type custom-built log house with a hot tub and a landscaped yard (done by Rico’s dad, naturally). I don’t know how she got home that night.

I don’t know what happens at Molly’s.

My house is a well-kept rancher that squats on a curving slab of subdivision cul-de-sac on the northeast edge of town. When we first moved here, we lived in a different well-kept rancher a little further into what used to be the edge of town when I was kid. Eventually, that edge of town just became town, as the town swelled past it and made new edges.

Where my house now jostles for space with a lot of other houses, it all used to be forest. When I was the previously mentioned kid, I and a lot of friends that have all disappeared from my life used to tear through those woods all summer, pretending we were Power Rangers. All the forest trails we made then are a whole bunch of backyards now.

When they made those backyards, though, they left the bigger trees standing at strategic points along the property lines. And if you spent as much time as I did orienting yourself to those trees when it was all forest, and if you remember the lay of the land that the subdivision roads follow now, you can sort of place the old view over the new view in your mind.

I’m not entirely sure, but at that younger age, I think I might have regularly peed against a large scrub pine that once stood exactly where our bathroom is now. This seems like a remarkable coincidence to me.

I open the garage with the remote clipped to my handlebars. Rolling inside to park my bike, I hit the remote again to close the door even before it’s rolled all the way up. I drop almost to the ground as I slip out, the door grinding down over top of me and slamming behind as I stand again. It’s a well-practiced ritual. Our timing is perfect, the door and I.

Inside my house, there’s a vaguely middle-class ambience. This vagueness speaks to the fact that I’m probably not really middle class, but more upper-middle-class-pretending-to-be-middle-class-to-keep-the-property-taxes-down. I hang my helmet and my jacket alongside the field of other jackets by the door. The only light on is at the stove, such that as I come in through the kitchen, an unearthly pulse of color wafts in from the living room beyond. I grab an apple from the bowl on the table as I pass.

In the living room, well-stuffed furniture fronts last year’s consumer electronics. Seth and Nora are glued to the TV that I can’t see from where I’m standing. Their chairs sit a carefully arranged distance apart, so that both get the precisely proper effect from the environment speakers buried in the wainscoting. It’s too bad that the environment speakers are currently pumping through AM radio, a pulse of tinny local call-in show barely registering where the TV sound is off.

Seth and Nora are my parents. Only Nora looks up as I wander in.

“Yeah, I did,” I say.

“You stow that [lord’s name in vain] bike away from my truck this time?” Seth barks.

“Sorry, I won’t.”

“Don’t be a smart-ass.”

“Hi, I’m home.”

Seth looks up at me then with a steely gaze. I eat my apple. I am calm because I know this steely gaze.

“You call this getting in early?”

“Had some work in the computer lab.”

“Had some more of your [lord’s name in vain] games to play with those [unpleasant anatomical reference] friends, you mean. Psychopathic [dung], Dungeons and Space Trek, whatever the [anglo-saxon expletive] hell you call it.”

“Yeah, that’s it.”

“What the [lord’s name in vain] hell you going to be, hanging out with [anatomically impossible act] satanists next? Mutilating [anglo-saxon] cows back of Bridge Creek?”

Hey, what I was talking about earlier? About not knowing where my predisposition for profanity comes from? Never mind.

“Nice work if you can get it,” I say as I head for my room.

The wash of light from the TV is overwhelming now, a strobe effect that gives the living room the feel of an underwater disco. It’s impossible to pass through the gauntlet of light for the hallway opposite without seeing. Like most nights, I catch a glimpse of satellite soft-core porn in widescreen HD perfection.

Nora is watching intently as she crochets. I feel suddenly distant as I say goodnight.

Hawkwind, 1981. This is surveillance footage, night-vision green. An abandoned mine site, dark.

Eighty-odd klicks roughly due northeast of town, the mountains past Hendrix Lake used to be full of molybdenum mines. Molybdenum is a metal that used to be important for manufacturing or something, and then stopped being important. Or maybe the market got cornered and bottomed out like markets always do. Either way, the mines and the satellite townships that served the mines all kind of disappeared or got turned into proto-resort communities for European tourists. The townships got turned into resort communities, I mean. The mine sites just turned back into the wilderness they’d been carved out of in the first place.

Most of the mine sites, anyway. But not this one.

A long way from anywhere, a nondescript stand of forest and scrub opens onto piles of rubble and tumbledown buildings, faint in the light of stars and the crescent moon. Tailings piles run down the mountainside, an overgrown road snaking off into the distance, strewn with boulders where the last of the heavy equipment blocked it on the way out.

From above, a low rumble builds. Then the darkness suddenly splits as the black chopper last seen soaring over Howie’s Corner Store drops from the sky. In its landing lights, decaying signage is seen — McIntyre Molybdenum — Pit 3. Smaller signs are set at intervals along razor-wire fence — NO TRESPASSING — MINE SITE UNSTABLE — EXTREME DANGER.

As the chopper descends to an abandoned mine face, more light flares from below. Carefully concealed doors slide back into the mountainside, a landing bay beneath them, and yes, it all looks just as James Bond as it sounds. Four other black helicopters sit there, silent as the first touches down. The bay doors slide back into place overhead, shutting to silence and shadow. Never there at all.

I’m watching interior audio and video surveillance, the feeds from six different monitor points painstakingly cut together to follow the conversation as it unfolds.

The space is an intricate interlocking of identical white corridors, well lit. The feel is of an anonymous office building, or the halls of some college humanities department without all the Canadian Federation of Students and Amnesty International posters on the walls. A mix of men and women pass by the static camera points that take it all in. Army fatigues are in evidence, but just as many wear sweatpants, t-shirts, and baseball caps. An informal air. Nothing that would arouse your attention or suspicion. Unless you know that the helicopter landing bay that just opened up out of nowhere on a mine site mountainside lies just beyond the double doors at the end of the corridor.

Through those doors, Lincoln, Karya, and their group emerge. Guards in night gear pass, automatic weapons at hand. Lincoln returns their salutes with a nod, carrying on with a conversation that I didn’t hear the beginning of.

“All right, European city you’d want to get arrested in.” His voice is American, threaded through with an easygoing drawl. The south somewhere, Georgia or Carolina or one of those.

“Paris,” Karya says, a sense of casual familiarity passing between the two of them. “There’s a great view of the Seine from the Palais de Justice holding cells.”

“Bucharest for me.”

Karya laughs. Even on the badly downsampled feed, you can hear a lightness to her voice. “Excuse me?”

“There are rumors circulating that Ceausescu’s personal chef is still serving a life sentence in the kitchens,” Lincoln says. He nods to more people as the group passes. “Seventy-six years old and he does a lamb pilaf to die for.”

“I think all that post-Soviet charm would overwhelm the ambience quickly.”

“I wouldn’t be staying long. Mr. Malkov, good to see you.”

“Good to see you, sir.” From the right, another figure falls into place as Lincoln walks, almost like he’s melted into view from the walls themselves. Combat pants and olive drab t-shirt, grey eyes so dark they look black. His hair is shaved almost to the skull, goatee a little longer. Mid-forties if you study him long enough. He looks younger otherwise. This is Malkov.

“Good to be back,” Lincoln says. “Long flight. Any developments since we spoke?”

“Sinai pickup operations at MFO North Camp are proceeding on schedule. There’ll be a two-day delay for Locke and Parillo to clear Syria. An intelligence cabinet meeting has been scheduled, they wanted to see if they could infiltrate.” Malkov’s voice has a military crispness to it that fits his look a little too well. “Our contact in Texarkana has confirmed receipt of down payment and has transfer set for June twelfth. The opportunity to move munitions as Red River closes down is looking very good. Also, our Kurdish client was in touch. He wants to know if we might speed up transfer of his Stingers. Some sort of action coming up, apparently.”

“You explained that his Stingers haven’t been stolen yet?”

“He seemed quite willing to discuss negotiation of an expedited arrangement.”

“Can we contact Red River, add some missiles to the shopping list?”

“Already done,” Malkov says.

When Lincoln smiles, it carries absolutely no humor.

“Business is excellent, then.”

Billy Squier, 1981. This is my bedroom. If you could see it, you might not get that fact all at once, because unless you look really closely, you can’t actually see the bed. It’s currently lost somewhere beneath a morass of books and papers, flowing down and across to the corner of the room where I’m sitting at the rolltop desk I got for my twelfth birthday. In the other corner of the room is the recliner where I actually sleep.

It’s a little before midnight and I’m still up, hammering away at the MacBook. Over and above me are two walls worth of posters that express the following sentiments (in order, from the door):

Boycott WTO-Doha

World Wildlife Federation Canada — Adopt a Polar Bear

Remember Love Canal

CIA Out of the Vatican

Vatican Out of the World Bank

You’re Gonna Die For Oil, Sucker

Rush: Hemispheres on sale October 29

Batboy on Secret Afghanistan Mission

On the opposite two walls hang poster-sized blow-ups of the most intense bits of the JFK Zapruder film. Seth and Nora haven’t come into my room in a while now.

With the last of the gluco-caffeine rush of five hours earlier, I’m typing madly to put the finishing touches on an article called Under Construction — 9/11 Pentagon Renovations and the Area 51 Cover-Up.

I’m not paranoid, all right? Just think about it.

At the edge of the desk, my iPhone rings ten times. I wait that long to answer it because the few people I give my number to know to wait that long. Breanne has long since refused to call me, saying it’s usually faster just to wait until the next time she sees me in person. I don’t use voicemail, because I don’t like the idea of some call center guy on the other side of the world having the same access to my messages that I do.

I’m not paranoid.

At the other end of the call, it’s Connor. I’m not sure if Connor is his first name or his last name, and whichever it is, I don’t know his other name. He’s the guy behind a conspiracy website/blog called Five Horsemen, which the article I’m working on is three days late for. Connor is ex-military security, deep ops intelligence for NSA/CSS in the States before he went to ground in Vancouver and started publishing. Intelligence community whistle-blower stuff, mostly.

That’s how much of his life story Connor lets people in on, at any rate. I tried to find out more once, a month or so after I first started writing for the site. I was half an hour into a web search on Connor when he emailed to tell me to stop doing web searches on him.

I’m not paranoid.

Five Horsemen doesn’t pay much, but it covers my phone bill and my net access, which Seth has been billing me for in the absence of being able to inflict any other effective punishments on me. He once decided I should start chipping in for food and utilities, but I just ate at Mitchell and Breanne’s for a week. That didn’t sit so well with Nora, so Seth backed down. I’ve long suspected that at some point, something I do will tick him off enough that he’ll start charging me rent. I figure I’ll blow up that bridge when I cross it, though.

Connor’s voice on the phone starts off strident, then is made more so by a stammer that can be taken for thoughtfulness if you don’t know him that well. Even three days late, I’m one of his more dependable writers, so I manage to slow his rant down before he gets into too high a gear. The two of us ramble on for a bit about deadline pressure and the telltale signs of laser audio surveillance, but none of that is really relevant to why I’m telling you all this.

Why I’m telling you all this, is that while I’m talking to Connor, my email icon jumps.

While I’m talking to Connor, I flip through to mail by reflex. I see a single new item caps-titled

GAME ONLINE AND WIN BIG!!!

My spam filters have a lethal degree of server-side precision that I programmed myself. I’m annoyed for a moment by the idea that those filters could be bypassed by someone who thinks three exclamation marks are an effective marketing tool. Two keystrokes are all it takes to log and blacklist the unopened pitch’s unseen routing info. The supposed sending address flashes past where I’m only half-watching.

play@vindicator.org

A tap on Delete and the offending text is gone from my inbox and my life.

I tell Connor he’ll have his piece in ten minutes. It’s actually an hour before I finish the final edit and send it off. It’s another hour after that before I finally sleep.

Part One — Also available in PDF

Sidnye (Queen of —

the Universe) —

Extras —

Short fiction and excerpts from longer works will be posted from time to time at the Insane Angel Studios site.

We Can Be Heroes — Available in ebook and trade paperback.